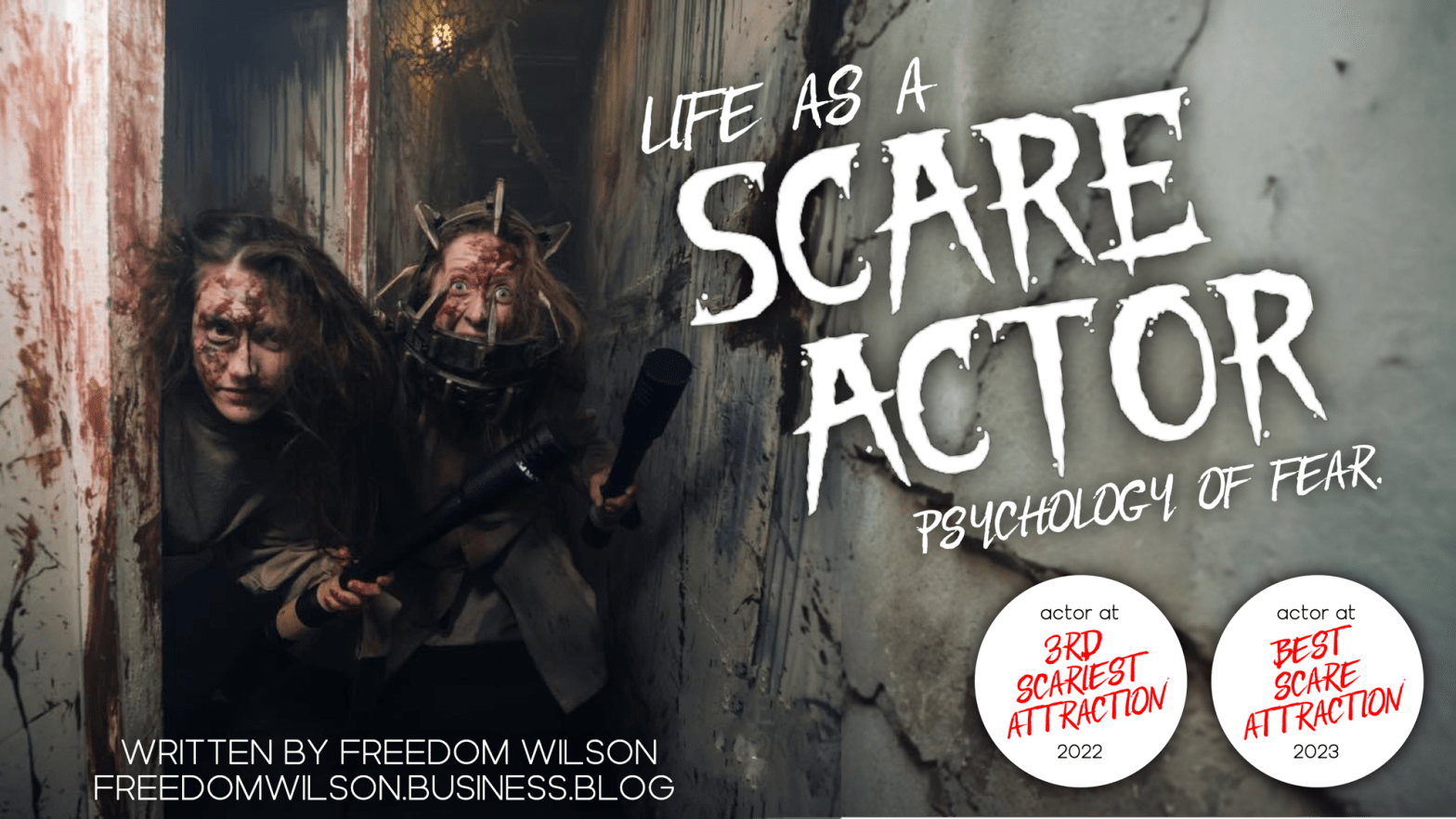

If you believed that Scare Actors/Actresses have effortless and straightforward jobs, you were mistaken. Being a fright performer involves a wide range of fear-inducing techniques, of which is grasping the psychological aspects of fear to deliver an effective scare. A psychological approach to fear is often overlooked. While some may think that actors at scare parks simply jump out and reset, for a select few, including myself, their mission is to deeply unsettle visitors at the scare attraction, immersing them in a psychological experience. In this passage, I’ll be guiding you through my journey as a scare actor and emphasise the demanding and challenging nature of this job.

This role can be effortless when you approach it with simplicity. But to truly comprehend fear, one must closely watch people’s responses. It’s not just the screams that induce fear in guests; there are numerous other reactions. The fundamental aspect of fear psychology revolves around customers recognition of a perceived threat, whether real or imagined, which initiates a cascade of reactions within the mind and body. This includes the activation of the fight-or-flight response, characterised by the release of stress hormones like adrenaline and heightened heart rate and alertness.

Among the most frequent reactions at a scream park is nervous laughter, where you may find yourself chuckling, laughing loudly to persuade others that you’re anything but scared, when, in truth, you’re deeply unsettled. Customers with tense hunched shoulders often indicate they’ve just had a prior encounter. They inhabit a heightened awareness of their surroundings and are attentive for the next scare. Some even avoid making eye contact, understanding that meeting your eyes will lead to regret.

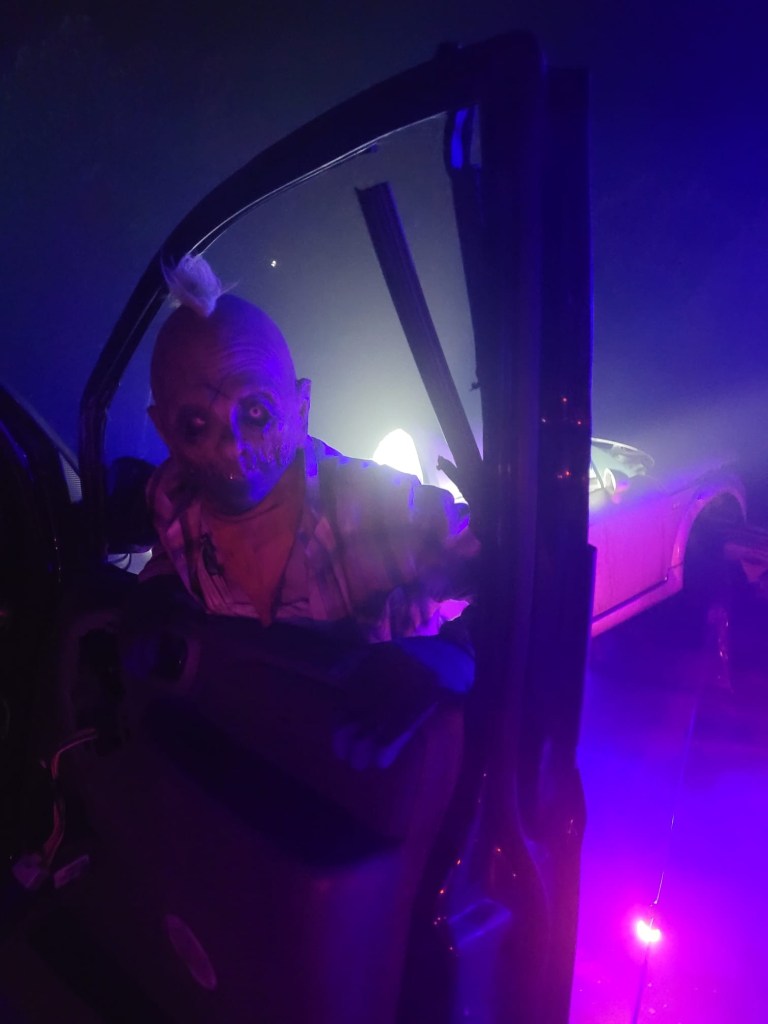

Unpredictability is crucial for every guest, causing them to underestimate the situation and the chances of a surprise. One primary technique employed by scare performers is the art of diverting attention or misdirection. For instance, I was stationed in a junkyard filled with discarded, wrecked cars. My jump scare involved leaping out of a van, which might seem simple, it was rather predictable given that the van’s door was wide open. Fortunately, I collaborated with another actor for this particular scare. He would be stationed on the floor to the left hand side while my van was on the right, leading visitors to navigate around him. As their attention is diverted away from the van onto the other actor they are completely overlooking the wide-open van with someone inside. Timing is the key for success here, allowing you to frighten the entire group if you’re fortunate. It demands patience and precision.

Now, you might wonder, ‘How does this work with just one person?’ It’s simple. Without the extra person, their focus is drawn toward the van. So, when they glance to their right into the van, that’s precisely when I’m right in front of them when they turn their head forward or to that effect.

Continuing the story in Junkyard, I’d like to introduce another aspect into the conversation – what I like to refer to as “going that extra mile”. Imagine the scenario I just described and consider how the guests are reacting. It depends on the guests, so let’s focus on those with tense shoulders and nervous laughter, like the example I mentioned earlier. Suppose they’ve already been startled by the actor in the other van ahead of ours, their shoulders are hunched or they are smiling, they’re walking cautiously and they feel exposed. Deliberately, I would take my time. They spot the other actor doing nothing on the floor so their shoulders begin to ease, and they regain their composure. This is the pinnacle moment to strike.

To then “go that extra mile” with these individuals, I would exit the van and follow along next to them as they head towards the chainsaw. It might not sound like much, just walking beside them, but after they’ve already been frightened, that’s when they’re at their most vulnerable and fearful. Their deeply rooted mindset is that once they have scared me, they have opened a gateway to scare me again, making them believe that the performance artists possess the capability to do anything. Often guests may say phrases like “leave me alone” or “stop” – for future reference, if you say this to a performer they will never leave you alone.

Another instance of ‘going the extra mile’ took place in Fortress, which resembled a prison. I portrayed a character known as Sack Head, yes I did have a full sack over my head. With this character I consistently pushed the boundaries. Placed on an electric chair, the potential for the electric chair scene was vast, involving vibrations, screams, and more. However, I portrayed this character as highly dynamic and theatrical.

As customers came around the corner, they’d come upon me resting on the chair, following eye contact with them as they moved, uncertain if I was a real person. Unpredictably, I would rise and stride toward the barrier in front of me, with immediate scares. But I took it ‘the extra mile.’ Guests often assumed one scare was sufficient, but when they were about to exit, I came toward them. Witnessing me approaching, that’s when they’d start running and screaming.

What if you can’t induce fear in someone? It’s a rare occurrence, most commonly with men, but there are alternative methods to terrify beyond the classic jump-scare and vocal approach. You can make them feel uncomfortable in themselves and their surroundings. Yes this is possible, it’s known as psychological mind games.

An instance of this arose during one of my auditions. Lacking any costume, mask, hair, or makeup, I crept toward a man on all fours towards his genitalia, just using my hands, knees and slight contortion, significantly similar to the ring characteristic. This alone made him uncomfortable due to my gender and resemblance to a figure already associated with fear. When costume, mask, hair, and makeup come into play, it’s a whole different experience. No one knows your gender; they just assume. In such situations, the most effective approach involves using your eyes. Regardless of your height compared to theirs, communicate with your gaze. People aren’t accustomed to being stared at or followed around every day, so you can turn this to your advantage. If you perform your role effectively, you might even witness tears. Even when you feel like giving up on a single guest, “going the extra mile” for 1-3 minutes will leave them uncomfortable, believe me.

In addition to yourself and fellow artists to interact with, another crucial aspect to consider is your environment, including lighting, visuals, smell, props, room layout, attraction design, and illusions. My favourite experience with these elements was in The Paradise Foundation. In this scenario, I portrayed a deranged mental patient armed with a taser, and the setting included a maze room, smoke machines, flashing lights, alarms, and one exit.

Positioned in the back room, we made the most of our surroundings to play with people’s minds. Given the maze-like layout of the room, I persistently took it ‘the extra mile.’ I deliberately chased individuals through the maze and blocking the exit to prevent anyone from escaping. I was so effective at keeping people ‘hostage’ that they would often wander around in circles up to three times or more. At certain points, there would be up to 60 people in the maze at once. When they finally reached the exit, I would unleash a cackling voice, shouting, “This way, that way, forwards, backwards.”. Frequently leading to episodes of panic, tears, urination, and vocal distress.

Theming is a crucial role in an attraction, demanding a firm grasp of the storyline and characters, unwavering commitment to the theme, and boundless energy. Beyond the actors, as previously mentioned, the layout is paramount. It should incorporate phobias such as claustrophobia, arachnophobia (fear of spiders), acrophobia (fear of heights), coulrophobia (fear of clowns), nyctophobia (fear of the dark), trypophobia (fear of clustered holes), hemophobia (fear of blood), thanatophobia (fear of death), automatonophobia (fear of humanoid figures or mannequins), ophidiophobia (fear of snakes), and necrophobia (fear of corpses or dead things).

Leveraging these phobias and fears effectively enhances the scare factor in attractions. The most prevalent among these for such events are claustrophobia, nyctophobia, coulrophobia and hemophobia.

Each visitor to a scream attraction elicits various responses, as I previously mentioned. Unfortunately this job entails encountering violence, such as guests screaming in the faces of scare artists for fun, attempting to physically engage with us, causing disruptions, and subjecting us to verbal abuse. If you deliberately attempt to engage with an actor or actress in an offensive way or reveal their hiding spots purposefully, it is extremely disrespectful. In such instances, performers often break character and refuse to perform. Guests who are considerate and respectful behind such individuals may have an unsatisfying experience because of their thoughtless actions and behaviour.

Fright performers, just like any other professionals, come from diverse backgrounds. Some engage in this for the enjoyment, while others, including myself, rely on it as a means to earn a livelihood through seasonal work in places like scare parks. Scare work involves more than just startling guests, despite what customers think. It’s crucial to treat them with kindness and respect during the spooky season. These talented individuals are paid to give you a thrilling experience, not to endure verbal abuse or physical harm. Remember, they are human beings, so show them nothing but love and appreciation.